Eboni Marshall Turman

The Reverend Dr. Eboni Marshall Turman contains multitudes. She is an assistant professor of theology and African American religion at Yale University Divinity School, the author of Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation, a preacher, and an activist. Her work revolves around the critical discussion of and question of how churches, and the world at large, treat and oppress Black women; along with the dissemination of Womanist Theology. Quite a mouthful, right? Please read on to discover how such an intelligent, driven, thoughtful, and rigorously academic mind enjoys and digests both fiction and non-fiction through the lens of activism, pleasure, and theology.

photography by Laurel Golio

Girls at Library: What was the name of the first book that you fell in love with that turned you into a lifelong reader?

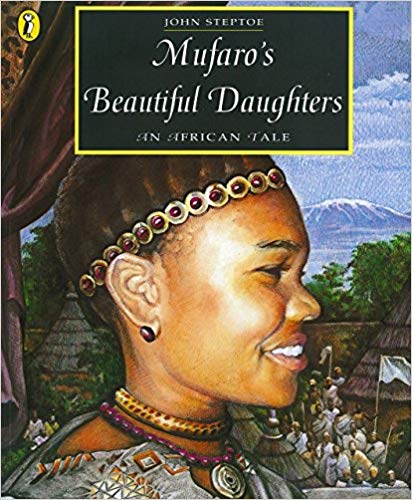

Eboni Marshall Turman: So this question is an interesting one, because I could say The Berenstain Bears collection, which I was reading pre-kindergarten and collecting. I became a collector of books very early on in life, and that is just the one series that I absolutely loved. Just recalling The Berenstain Bears gives me warm feelings of home and peace and calm. I loved them. But I also distinctly remember from childhood this book called Mufaro's Daughters. And I wanna say it's by John Steptoe, and it was a picture book though it was a bit more advanced than The Berenstain Bears. It was a story of these African princesses, and their father, and it was my first memory of seeing Black girls, you know, in a book. And so I loved that book. I read it over and over and over again. That was somewhere around first or second grade. Somewhere between second and fourth grade, I probably read Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.

GAL: That is one of the most remarkable books I’ve ever read.

EMT: Oh yeah. I think that one just sealed the deal for me. Not only did that book seal the deal for me as a reader, so not only reading for the enjoyment of the story, but reading as a cultural activity, as a cultural journey. Mildred Taylor probably sealed the deal on that one. So those would be kind of the three childhood-like stages that did it for me. But I could name so many more, right? Like the Fear Street series. I absolutely love thrillers. Did you read "Fear Street?"

GAL: I didn't, but I loved the ‘Goosebumps’ series and read a lot of Stephen King when I was really young, which was maybe not the best thing for my imaginative brain.

EMT: I think I did that too, for sure. And then I started having nightmares and had to stop.

GAL: Why do you read?

EMT: First of all, I think, on a very personal level, reading calms me down. It really functions as an escape into peace for me. I read before I go to bed. When I read before I go to bed, I always have a better night's sleep, unless it's Stephen King, of course. But it's an escape from living the kind of life that I do, which is very, very busy and very engaged; politically and culturally engaged. Reading offers me an escape, a retreat, from what's actually happening. On a larger scale, reading helps us to inhabit worlds that are not our own. It helps us to come into contact with the unimaginable, with the impossible.

And that, especially as a religionist, as someone who is always thinking within the world, but thinking beyond what is; there's a real comfort in that. In being able to touch the impossible, the unimaginable, through the power of story.

GAL: Yes! Can we speak more specifically about that power? How have fictional narratives impacted you and your life? Or, as a religionist and an academic, how has non-fiction impacted you?

EMT: Well, I think about stories like Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, and every Toni Morrison book ever. The Color Purple by Alice Walker. I think about reading as a cultural exercise. So, the way in which reading allows me access to the stories of women, especially, and of Black women, that are particularly my story, is key. Stories that I carry in my body, but don't necessarily have my own words for. Reading gives me access to those kind of impossible words, and I think, in accessing these stories, especially women's stories, it gives me a certain kind of reserve for when and how I feel it in my reality. How I can walk in and through challenges, negotiate challenges, persevere, and create for myself and for my communities. The power of story is the fact that it gives us resources. Stories are themselves resources that show us the way, that show us how we might live, how we ought to live, what we might do in our own realities.

GAL: Did you spend much time at the library while you were growing up? By yourself or with family?

EMT: Absolutely, absolutely. There was a library very close by all of my life, all of my growing up. I have very early memories of my mom taking me and my brothers to the library. We went once a week. I remember the excitement of getting my first library card, I think I was around five or so. Before that though, of course books were always a thing in our home. They were just always there. When I think about school libraries, I was introduced, I think, to Judy Blume, and I'm thinking specifically, Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret, in the library of my Catholic elementary school, so yeah. I've been reading forever, and the library was a thing, and in the summer time, my brothers and I, we had to write book reports every week ...

GAL: Oh my god, every week! Why? Did you parents enforce that, or were you driven to do such a thing?

EMT: Yes. Every week. Our parents enforced that. The books we got from the library, we had to report back on what we had learned, what we had discovered in them.

GAL: How important was religion in your family while you were growing up?

EMT: Religion was also special for my family from very early on. My mother made sure that all of her children were in church fairly regularly. So it was a thing in our household, and my church – actually the First Baptist Church of Crown Heights – started in my aunt and uncle's living room. My Uncle David and Aunt Camilla were founders of that church. The concept of God has always been a living concept in my family, and growing up, and church was also something that happened regularly. I went to Catholic school in elementary school, so I was kind of conditioned to think about religion and morality very early on.

GAL: The writer Dorothy Sayers, author of a book titled ‘The Mind of the Maker’, said: "We're made in the image of God. And what is God? God is a creator." What do you think about that statement? Do you agree or disagree?

EMT: I write about the image of God, so this is an interesting question. I think that fundamentally, and in relation to the idea of creativity, yes. I agree with that statement. But I will say that when we think about the actual statement, the idea of image, and being made in God's image, that one: for women that message may be historically a hard pill to swallow, like hard thing to live into. For Black women it’s especially hard. Based on the fact that not only is gender at stake, but also subordinate descriptions- like the ideas of Black bestiality, sub-humanity, and all of that. So, we think about the image, and image being some kind of visual mechanism. It’s hard to embrace that statement because God has historically and typically been imaged as a man. And as a white man at that.

GAL: So who is God to women? To Black women?

EMT: Hm. Well, I think that's a very big question...

GAL: Yeah, I'm sorry, I'm really sorry. This is an example of something that came up in my own self-criticism today. I was like, "You need to not ask such wide-ranging, big questions, Payton Turner." So let me share the path of the question, the scope, and see how you’d like to answer it.

EMT: Sure, sure, sure. [laughter]

GAL: How do you define a woman's place in the church today, and does your definition match the church's definition? Who is God to women? Why is God important to you? Why should God be important to women and Black women today? Sorry.

EMT: That's a lot. Geeze, Payton, what are you doing? [laughter]

GAL: I told you I wanted to talk about this stuff. Hit me.

EMT: Alright, so let me just say, first of all, that when we talk about God, or when we engage God talk, I want to be explicit in saying that I'm responding to your questions from a Christian perspective.

GAL: Yes. Okay.

EMT: As a Christian theologian, recognizing that religion is bigger than Christianity, and so for as many religious traditions as there are, there would be some distinctive responses to the question, "Well, who is God?" Or, "Who is God for Black women?"

GAL: Yes.

EMT: I think one aspect that could potentially animate many of those responses across religious distinctions is the idea of spirit and the way in which God manifests as positive spirit. As a spirit of love, and of peace, and of justice, and of hope which helps us to live together, and helps us to be better people for each other. So I think that that kind of wondering broad way of thinking about who God might be for women and who God might be for women across religious distinctions. I think about God from the Christian tradition, and specifically from the tradition of the Black church, I think of God as, like my grandmother would say; God is a friend to the friendless, God is a mother to the motherless, a father to the fatherless. In my tradition, we say something to this effect: God is a way-maker, you know?

GAL: That’s a pleasing way to describe it.

EMT: And so God is our help, God helps us. And so along with the more classical understandings of salvation and redemption and creator, a creation, and comforter, right? So there are all of these things floating together. I also think that, with that liberated understanding of who God is, God is a liberator, you know what I'm saying.

GAL: I think so.

EMT: You know, there's this idea that God has also been transmitted to us. So God is all of those things, but God has also been transmitted to us as this angry person up in the sky judging everything we do, right?

GAL: Yeah, that sounds right.

EMT: And who has a special affinity for men, and a special kind of disgust for women. And sexual minorities, our LGBTQ kin, right?

GAL: Yeah.

EMT: So I think that in the church, women often land somewhere between those two poles when they think about, "Who is God," right? These understandings of God have, throughout the centuries, have had very devastating, traumatic effects on women and still continue today. In terms of the way that women are subordinate to men in many Christian traditions, for example. Also through very pedestrian practices like, even though women make up approximately 90% of church membership, you still have rules like women can't be ordained, women can't be priests within Roman Catholic tradition, they can't stand on the pulpit, women have to wear skirts and you have to wear pantyhose. And it gets even deeper than that. So there are all of these very sexist and misogynistic and, for Black women, specific traditions and practices at Black churches that are very detrimental to women. I think that this is why I believe it's important for me to do the work that I do, as a woman theologian, so that I can think deeply about religious traditions, Christian traditions, Christian doctrine, and the church, to offer another interpretation of these traditions, of doctrine, and of women's role and women's power for religious leadership contemporarily speaking.

GAL: Now I understand how you reconcile all the things you focus on, especially in terms of women, God, and the church. What you're trying to do is a huge job. It also makes me less terrified of the institution itself, hearing you talk about it.

EMT: Yeah, well, it's terrifying.

GAL: Yeah. It really is!

EMT: It's terrifying at the best of times, and when we think about the political situation now, when we think about Roe v. Wade, and the Supreme Court, and we think about…well, I mean, just everything, you know? When we think about everything, there's always this religious, moral element guiding political decisions, and those tend to be the component that is rooted in the control of women. That itself is driven by patriarchy.. Religion is supposed to be that place where no one can push back, no one can ask questions, it just is what it is.

GAL: It's the law.

EMT: This is what God says, right?

GAL: Yeah, I think so.

EMT: Right. We can have the most accomplished, amazing, powerful, feminist women in the secular world, in their jobs. They're presidents, they're CEOs, and founders, and principals. But they go to churches where women can't be ministers. And it's like, no! We, as women, have to continue doing the work of talking back to these patriarchal, misogynistic, and racist traditions, and calling BS.

GAL: Do you think through that kind of work, it's possible to change the structure around and the perception of how women are treated in the church?

EMT: I do. I'm a beneficiary of women who came before me who challenged and pushed, kicked down, and broke stained-glass ceilings. I didn't just decide to do this one day. Even though progress has been slow, relatively, I have to believe that we can transform. We can, I should say, resurrect the church. Or else I wouldn't be doing the work that I've been doing.

GAL: Do you think that the role that the church plays in Black communities will change in the next five years? Maybe 10 years? Part of this question is how has the Internet impacted faith and religion?

EMT: There have already been significant shifts. It’s hard to say. I absolutely think that there will be changes, like the Black church will continue to change, the church will continue to change. The Christian church is just being affected by the times, and by the fact that community functions very differently in 2018 than it did in 1950. Maybe so many churches will continue to be modeled on that mid-20th century, even to late-20th century, model of ministry that is still important, but methodologically irrelevant. I think the church will continue to have to grapple with how to meet the needs of a now generation that looks very different from the boomer generations. The church has to be willing to reinvent itself. Some would argue that the church is undergoing a reformation right now, actually. Of course we won't know that until 200 years from now. The church has shifted over the years, and so this is just par for the course, if the church is going to live. Which it will. I am absolutely convinced that it will. It will have to reinvent itself to meet the people where they are.

GAL: What do you think Future Church might look like? Chat rooms? How might it function?

EMT: Yeah, that's kind of scary, actually. I think that a lot more will happen online. I think it will be important to always have a brick-and-mortar church house, but I do think allowing church goods to be accessible outside of the brick-and-mortar will be important. So that means there will be more online access to preaching and sermons to Bible study, to community, and "chat room," is an interesting choice of words, but maybe online, virtual small groups, virtual meet-ups, things of that nature. I know that Sunday holds relevance for the Christian church, but we may have to rethink when we meet, how we meet, is church a three- to four-hour engagement, right?

GAL: Right. Attention spans have changed.

EMT: We might have to just spend 45 minutes to an hour instead. Also, what types of art are we using liturgically? What are the ethics of appearance that function in our church? Are we tied to, again, a 1950’s aesthetic, or are we open to something else? I think that life cycle has to be engaged. We no longer live inside a context where people graduate from high school, get married, and start having children immediately. Not even a context where people graduate from college, get married, and start having children immediately. Or if they have children at all! Thus those kinds of youth focused groups, Sunday school or family ministry, might no longer be the same model as it is now. It doesn't sustain the actual choreography of young adults who now stay young 'til they're in their 40’s. People who may not marry at all, who may marry later, who may not have children, who may have children later. Also, people who are not going into jobs where they stay in one place for 40 or 50 years, who instead change employment locales every two to five years. Thus, how is the church going to think about and deal with that kind of mobility? What about the change in life cycle that accompanies this new world that we're living in? I think addressing or constructing ministries that tap into that will spark the interest of people and really get them excited about serving God in the context of a church community.

GAL: Speaking of past times, you studied dance and were a dancer. How does dance fit into your life now?

EMT: Yes. I was actually a professional dancer.

GAL: You write and speak so much about the body, and spoke about God and flesh image before, so I wonder how it all ties together.

EMT: Dance inspires everything I do. My body is no longer 17, it's no longer 20 anymore. So my body doesn't do the things that it used to do, but my mind is dependent on dance composition, so when I write, I'm writing according to the method of dance composition. Theme variation. As a theologian, I'm very interested in performance art. I'm interested in Black aesthetics, and theological renderings of the body. Much of my non-fiction reading is committed to understanding the theory behind art, especially dance, and performance, and to thinking about that theory and thinking about the practice of the body, theologically. How God is revealing God's self in the body, which is a very Christian fundament. God comes to us in the body of Christ. But also, thinking about how the body is positioned, or is choreographed, to channel the sacred and the things of the sacred. Yeah, so dance is incredibly central to everything I do, even though I don't, unfortunately, find myself in dance studio as often as I would like to be there, and certainly not on anybody's stage. But I try to get one dance class in per week. It’s something that just doesn't happen, but I try. And I am a yoga and Pilates fanatic.

GAL: It's important to use your body, and think about your body in space in any capacity.

EMT: Well, absolutely. And also, the body and the mind are not these two separate things, even though doctors would tell us otherwise. Even though traditional, male perspective says, "Oh, there's this separation." The rational and the emotional, right? But that's not actually true. It is only deep interconnection, and so I feel that when I am engaging my body, in very physical and performative ways, my mind is functioning at 100. And similarly, when I take the time to stimulate my mind, it strengthens the ways in which my body can show up in the world. Which is where I've started right?

GAL: Yeah.

EMT: It’s a language, like reading. Reading helps us to show up in the world in different ways. And I think dancing helps us to tune into our mind in very interesting, creative ways. So yeah, they're like Frick and Frack for me, they just belong together.

GAL: Why are rituals important? And are there any ceremonial ways you go about reading?

EMT: Ritual, I think, calls us to remember. Ritual calls us to embody story. Especially when we think about religious ritual. All religious rituals are attached to a certain kind of story, and certain mythos, and these stories are reminders embodying memory, are reminders of our "why" right now. It’s so important to remember the “why.” Especially when the world is moving a million miles per minute, and there's many social and political challenges that are visited upon us women every minute of every day across all mediums. Meaning, even if we turn off the TV, especially us Black women, we are subject to any manner of violations, always, in everyday life. And so we can forget. It's easy to forget who we are, whose we are, why we are here. Our identity, our purpose, and the passion that drives us. And so I think ritual helps us to remember all of that. And it's so interesting, because I don't know if I have a ritual for reading for enjoyment. I don't light a candle. I kinda do for reading for work, but I don't like lighting candles for that, I kind of just plop down somewhere.

GAL: Yeah!

EMT: I think that reading itself is ritual for me, because when I'm reading, no matter what I'm reading – not like the cereal box, but – I read for work, so I read like six hours, six to eight hours a day on a good day, and then less than that on a not-so-good day. When I'm reading, whether it’s fiction or non-fiction, for pleasure or for professional work, I'm reminded of who I am, my purpose. Something about reading always says "This is who you are." I would have to say that no ritual accompanies reading because, for me, reading is ritual.

“Oftentimes, I’ll have students who have never even read a black woman.”

GAL: Why do you, and why is it, important to teach ‘The Color Purple’ in your theology class?

EMT: I use it specifically for my class on Womanist Theology, which is my course at the divinity school. I am the only Womanist theologian at the divinity school, though there are two other Black women at Yale Divinity School who are amazing and doing amazing work, but my work is slightly different. The book is the sacred text of Womanist theology because of how it offers such keen insight into the lives of Black women, and to the substance of Black women's suffering, and Black women's self-liberation. And finally, when you think about Black women suffering, what The Color Purple does, is it allows us to see the way in which Black women’s suffering is so distinct from that of white women or Black men. The two primary groups that people want to lump Black women in with, precisely because Black women so often suffer because of, and/or at the hands of, white women and Black men. The clarity and precision with which Alice Walker (although she is rightly mired is controversy right now) allows us to see this and to experience this Black woman's story, this Black girl’s story, this girl-woman's story through Celie, and Miss Sofia, and Shug. It's so clear, and so it holds so many of the theoretical and methodological tenets, and framework, of Womanism. It holds it right at the heart of the story. I mean, you can teach the theory, and the method, of Womanism and Womanist Theology, through the letters that Celie is writing to God and to other people. You can teach this very deep, very complex subject matter through this story. This is our book. It is essential for Womanists. The Color Purple presents us with the language of Womanism, gives us the definition of "Womanist," and Womanist prose.

GAL: How does it empower women to read other women? If you would rather speak to how does it empower Black women to read Black women, that's also fine.

EMT: No, because I teach everybody.

GAL: Okay, of course.

EMT: Especially at Yale. I have more white students than Black students. So I'll say this: it's very rare to walk into a classroom anywhere, and I should say, a theological classroom, and have the core text, the central text for the semester be a Black woman's novel. It just doesn't happen. Oftentimes, I'll have students who have never even read a Black woman.

GAL: What? At all? At Yale?

EMT: And even more than that, they had never been taught by a Black woman.

GAL: Oh my ...

EMT: That's real. So, I think I’ll answer: how does it empower Black women to read Black women. I think that, in the first place, for women who have not had the privilege of learning while centering women's voices, of learning while centering Black women's voices. It is a thing. Recognizing, then, that your voice matters. What you have to say, your life experiences, actually hold within them a way of knowing that is unique and powerful and able to change the world. And that's probably the biggest thing. As a theologian, I would add to that that women's voices have something to say about God. And this is not a man's Heaven and a man's Earth, right?

GAL: Right.

EMT: Women have been talking about God for a long time, and have been saying very important things about who God is, and who we ought to be in light of who God is for us. And believe it or not, that's a novel idea for many women, especially those who come from traditions that tell them that their brothers matter more than them. So I think that that’s one pedagogical intervention for teaching Black women through Black women's writing in the theological fashion.

GAL: Do you have a favorite theologian?

EMT: I have a number of theologians who I love. But I'd like not to frame it that way. I think women's theology, which is my area of concentration along with Black theology and liberation theology, Womanist theology actually begins outside of the text. In other words, my favorite theologians tend to be women who would never, ever think about sitting in a theology classroom or have never, ever gotten any kind of credential in theology. They wouldn't be considered anyone's theologian, but they are the greatest theologians. I think of people like Katherine Dunham and I think of people like, Fannie Lou Hamer and I think of people like Toni Morrison. I think of people who would never, necessarily, understand themselves to be doing theology, as some of my favorite theologians, because God talk is everywhere. If we have eyes to see it, ears to hear it.

GAL: What books bring you joy right now?

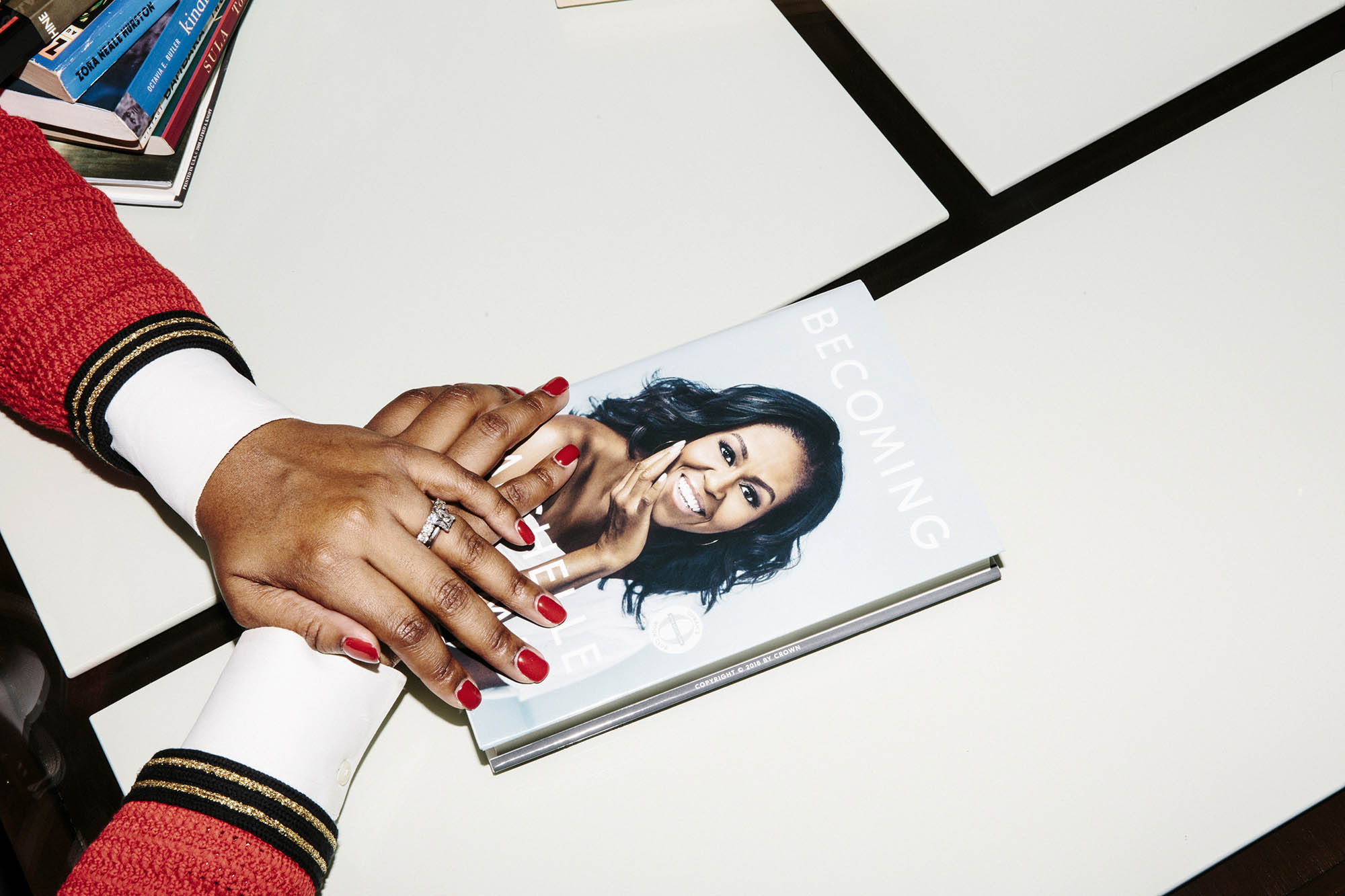

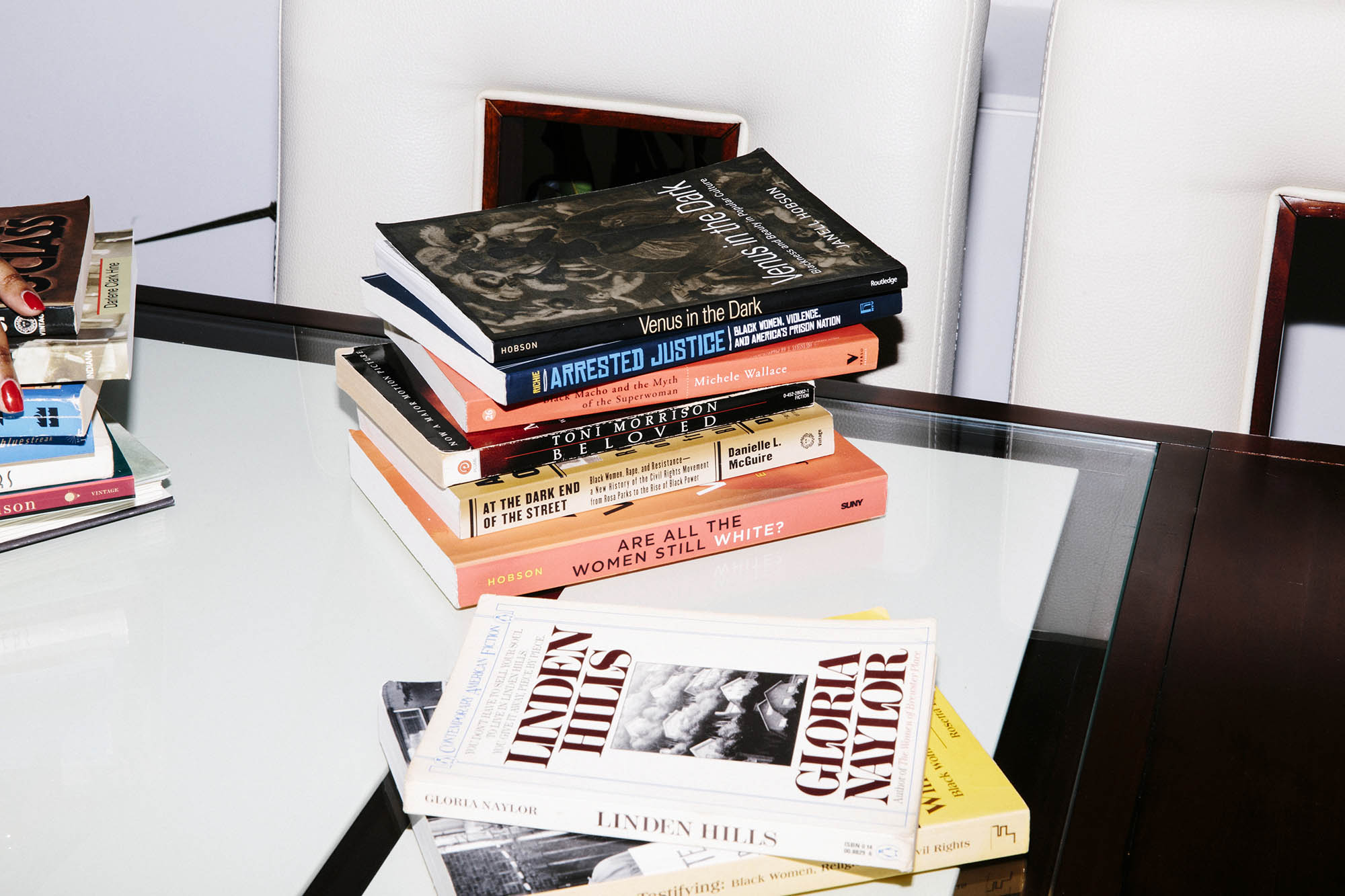

EMT: Oh goodness, well, I'm reading a bunch of non-fiction right now. A fiction book I just finished, for book club, Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine, is laugh-out-loud hilarious. It was such a great read, so that book brought me a lot, a lot, a lot of joy. Let's see, what is right in front of me right now: I'm working through Kelly Brown Douglas', for like the 25th time, Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. I'm working through Daphne Brook’s Bodies in Dissent. I don't really like her, but I'll just say this one anyway. Susan Juster’s Sacred Violence in Early America. So those are really, really good, really great books. I'm also reading Becoming by Michelle Obama.

GAL: How do you like ‘Becoming’?

EMT: I'm not sure if it's bringing me joy yet. I've just started it. I might be on chapter 10 or something, very early in the book. I'm trying to figure out how I am experiencing the book amidst all of the hoopla in the public square around it. I'm trying to get in touch with how I'm experiencing the book, and don't really have words yet for it. But I'm working my way through it, and I guess what does bring me joy about the book is how, even in this early part of the book, she's still talking about her days in high school, and in so many ways I can see myself in her. That's not something I can often say. I don't see myself reflected in true stories often. I see myself reflected in fiction, but not always in the non-fiction memoir category. So that's in a place of joy. Oh, I'm really excited about Brittney Cooper's Eloquent Rage. The way she goes in on just about everybody in that book, it's everything to me. I really appreciate the work that she's doing.

GAL: We have a friend who has something called a “Sanity Shelf,” where she keeps books that she returns to for knowledge, solace, and pleasure. What would be on your sanity shelf?

EMT: The Holy Bible. The King James version, because the King James version matters for Black Christians, I should say. I would, so the Bible would be there for sure, on my sanity shelf. I have James Cone's Black Theology and Black Power. The Color Purple by Alice Walker. I'd have probably Morrison's Song of Solomon. Maybe Toni Cade Bambara's The Salt Eaters. Maybe I would have Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine, too.

GAL: I'm really enjoying ‘Eleanor Oliphant’.

EMT: You know, there's so much in that book that reminds me of myself. I'm the weird person who will walk into a room and say exactly what I think. People will be like, "Did she really say that?" I also use very strange words sometimes. Anyway. It's an interesting story. Yeah, that would be my sanity shelf for now.

GAL: Is it important for you to physically hold a book, or can you read on devices?

EMT: It depends. I can do both. I typically cannot read non-fiction on a device. I have to hold the book, I have to be able to live and love and touch and feel the book with my body. I can read fiction on a device, even my phone, which is often what I do when I'm riding the train. But interestingly enough, for our Book Club books, I have been getting the hard copies, and kind of living with them, you know, living with the materiality of them in a different kind of way. Which has been interesting. I don't have space for all these books.

GAL: Where is your favorite reading spot right now? Do you have a favorite spot to read fiction and one for non-fiction? Or do you read on everything in one place?

EMT: I pretty much read everything everywhere. My favorite reading spot is my bed. I love to read in bed. There's just so much comfort in my bed, I'm always on the move, so being able to be in my bed is the ultimate state of relaxation. I'm not the type of person to fall asleep while reading, I will say, "Oh, it's time to fall asleep now, let me close my book," typically. I can read anything in the bed. It's better for me to read academic non-fiction at a desk or table or somewhere, just to keep me physically involved with, keep my mind kind of physically connected to the task of retention and not just enjoyment, yeah.

GAL: That makes sense, and I feel like there's definitely a mind/body connection to those preferences as well, like you mentioned before.

EMT: The bed is a space of enjoyment and retreat, and that's what my body feels. The desk, or the table, is a space of, "You need to remember this so you can talk about in five minutes," you have to work tomorrow.

GAL: What is the working title of your next book and when will it be published?

EMT: The working title is; Black Women's Burden: Male Power, Gender Violence, and the Scandal of African-American Social Christianity. I'm hoping within 18 months.

GAL: We’ll need to have you back on the site! After writing that book, if you were to then write your memoir, what would you title it?

EMT: If I were to write my memoir, I would title it "The Light Shines In the Darkness."

GAL: Please name a few theology books that are accessible for readers who would like to learn more but don’t know where to start.

EMT: Womanism and the Soul of the Black Community by Katie G. Cannon, Black Theology and Black Power by James H. Cone, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk by Delores S. Williams, Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil by Emilie M. Townes, Learning to Walk in the Dark by Barbara Brown Taylor, and Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God by Kelly Brown Douglas.

GAL: Thank you. And finally, I promise I won’t make you list anything else after this, what three books should every GAL reader read right now?

EMT: Sure. Eloquent Rage by Brittney Cooper, Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry by Imani Perry, and Moses, Man of the Mountain by Zora Neale Hurston.